Reexamining the Need for Corporate Bonds

A number of articles were written at the end of 2008 noting that, for the prior 40-year period, stocks had barely outperformed safer bonds.

For the period 1969 through 2008, the S&P 500 Index returned 8.98% and long-term (20-year) Treasury bonds returned 8.92%. Results for both large-cap growth and small-cap growth stocks were even worse. The Fama-French large-cap growth research index returned 8.52%, while the small-cap growth research index returned just 4.73%.

Making matters worse, while producing nearly the same return as long-term Treasuries, the S&P 500 Index experienced far greater volatility. Its annual standard deviation during this period was 15.4%, compared to just 10.6% for Treasuries.

That equities could outperform Treasuries over a 40-year horizon by just 0.06 percentage points (and that’s before implementation costs) surprised many investors, but it really shouldn’t have. No matter how long the horizon, there must be at least some risk that stocks will underperform safer investments.

Another Absent Risk Premium

Another risk premium also failed to appear over this same 40-year period, one that received far less, if any, attention. Specifically, there was no corporate credit risk premium.

From 1969 through 2008, 20-year corporate bonds returned 8.48% a year and underperformed 20-year Treasury bonds, which you’ll recall had returned 8.92%. Having no corporate credit risk premium at a time when there also was no equity risk premium shouldn’t especially have surprised investors either, because corporate bonds are really hybrid securities (a mix of the risks found in stocks and Treasury bonds). In short, they don’t contain all that much unique risk.

However, what may perhaps be more surprising is the following: For the 92-year period of 1926 through 2017, the riskier S&P 500 Index provided a significant return premium over safer long-term Treasuries, outperforming them by 4.62 percentage points (10.16% versus 5.54%). Over the same period, riskier long-term corporate bonds outperformed safer long-term Treasuries, but only by 0.52 percentage points (6.06% versus 5.54%).

Corporate bonds represent a significant fraction of the world’s capital markets. Looking at the Barclays Global Multiverse Index, which essentially encompasses the global fixed-income market, investment-grade corporate bonds account for $11.3 trillion of the $53.6 trillion value of securities included in the benchmark. High-yield corporate bonds represent another $2.5 trillion.

Taken together, this means investment-grade and high-yield corporate bonds make up about 26% of the global fixed-income market. Yet as the following evidence shows, the case for owning corporate bonds, particularly for individual investors, is weak.

Research On The Credit Premium

My colleague, Jared Kizer, chief investment officer for Buckingham Strategic Wealth and The BAM Alliance, examined the data and shows that portfolios owning equities and government bonds already are exposed to the risks corporate bonds provide, rendering corporate bonds redundant in most portfolios. The following is his analysis. (For those interested, you can find Jared’s paper, “Re-Examining the Credit Premium,” on SSRN.)

Barclays remains the best source for virtually all kinds of fixed-income data, certainly for investment-grade corporate bonds and high-yield corporate bonds. Barclays has index data going back to January 1973 for investment-grade corporate bonds, and back to July 1983 for high-yield corporate bonds. Jared used returns data for both indexes, along with index data for global stocks and bonds, to better understand whether either investment-grade or high-yield corporate bonds have improved the risk-adjusted returns of portfolios.

It is important to understand how much higher, historically, investment-grade and high-yield corporate bond returns have been when compared to Treasury bonds of similar maturity. This difference is the credit premium, meaning it represents additional return corporate bond investors have earned in exchange for owning corporate bonds versus safer Treasury bonds.

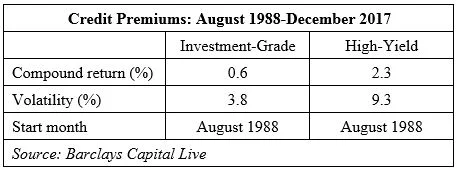

The following table, taken from Jared’s paper, reports various statistics associated with the investment-grade and high-yield credit premiums going back as far as the Barclays data permit. Barclays began explicitly reporting monthly credit premiums associated with both investment-grade and high-yield corporate bonds in August 1988, so this is the start date.

First, think about what the investment-grade column is showing. The figure 0.6 means that even though investment-grade corporate bonds have tended to have a yield advantage well in excess of 1% compared with comparable-maturity Treasury bonds, the historical return advantage has been only 0.6% per year. A significant amount of the initial yield advantage is lost to downgrades (bonds sold after falling below a BBB credit rating), defaults and companies exercising call options. Also, keep in mind this is before accounting for any costs associated with buying, selling and managing a portfolio of bonds.

For high-yield corporate bonds, the credit premium was 2.3% per year. The yield advantage again tends to be significantly higher than the return premium, with the difference explained by yield lost to defaulted bonds and the exercise of calls. As with the investment-grade results, these figures do not account for costs associated with buying, selling and managing a portfolio of bonds. Further, the long-run reward has been highly volatile, at 9.3% per year, indicating the risk-adjusted returns associated with the high-yield credit premium have been relatively modest.

Portfolio-Level View

While the preceding data is useful, portfolio theory is about portfolio-level returns and risk, not the results of the portfolio’s individual holdings. The basic question an investor needs to answer is whether portfolios historically have been better off holding investment-grade or high-yield corporate bonds if those portfolios already hold a globally diversified portfolio of stocks and government bonds.

There are several ways to attack this exercise, but each approach will give basically the same result if done accurately. For the exercise here, Jared starts with two portfolios, one that allocates 60% to stocks and 40% to investment-grade corporate bonds and one that allocates 60% to stocks and 40% to high-yield corporate bonds.

For both portfolios, it’s possible to answer analytically whether a third portfolio that only includes stocks and government bonds has provided a similar or better historical risk/return profile.

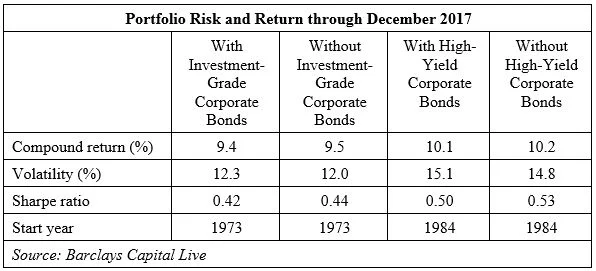

The following table from Jared’s paper shows the key results. For global stocks, he used a series that is a 60%/40% combination of the S&P 500 and MSCI EAFE indexes; for government bonds, he used the Barclays Treasury and Long-Term Treasury indexes.

In both comparisons (the first two columns for the investment-grade comparison and the last two for the high-yield comparison), the analysis shows portfolios that only include stocks and government bonds are capable of delivering a similar if not a slightly better risk-adjusted return profile when compared with portfolios that own corporate bonds. Again, this is before considering implementation costs.

The portfolio compared with the one that owns investment-grade corporate bonds allocates 68% to global stocks, 26% to the Barclays Treasury Index and 6% to the Barclays Long-Term Treasury Index. The portfolio compared with the one that owns high-yield corporate bonds allocates 85% to global stocks and 15% to the Barclays Treasury Index.

In both cases, this indicates that marginally increasing the stock allocation reproduces the basic result that corporate bonds would otherwise provide. This should not be surprising, because credit risk is one of the primary risks driving the returns of stocks as well as corporate bonds.

Additional Negatives To Consider

The expense ratios and trading costs associated with portfolios that own corporate bonds individually or through funds will generally be higher than the comparable costs for a portfolio of stocks and bonds. This is primarily due to higher trading costs in corporate bond markets compared with stock and government bond markets. In addition, for investors who have a majority of their investable assets in taxable accounts, holding corporate bonds in these accounts introduces avoidable asset location inefficiencies.

The preceding results suggest that most individual investors should think carefully before allocating significant assets to either investment-grade or high-yield corporate bonds. Portfolios that include only stocks and government bonds appear to span the spectrum of return and risk that capital markets have provided, while also generally having lower underlying costs and offering better tax efficiency.

Jared’s results actually understate the case for avoiding corporate credit risk, at least for individual investors who have access to the CD market. FDIC-insured CDs, which also have no credit risk (as long as you remain within the limits of the insurance), typically carry significantly higher yields that likely would more than wipe out the advantage in yield corporate bonds have over Treasuries.

For example, on May 3, 2018, the yield on five-year Treasuries was 2.77%. CDs of the same maturity were available with a yield of 3.25%, an improvement of 0.48 percentage points. Recall that, as shown in the first table, investment-grade bonds have provided just a 0.6 percentage point higher return than Treasuries. That would leave just 0.12% for implementation costs. After such costs, the investment-grade bond credit premium relative to CDs would likely be negative.

In addition, CDs don’t come with corporate bonds’ call risk. (Martin Fridson and Karen Sterling’s 2007 study, “Original Issue High-Yield Bonds,” found that call risk was a negative contributor to the return on high-yield bonds.) Another benefit of CDs relative to corporate bonds is that CDs often have very low early redemption penalties, allowing investors to benefit from rising interest rates, which is the opposite of what happens with corporate bonds. However, we are not done yet.

In Taxable Accounts, Taxes Matter

Interest on U.S. government obligations is exempt from state and local taxes. Interest on corporate bonds is not. Thus, if investors reside in a place with a state income tax, a taxable investor would require different yields from a Treasury bond and a corporate bond of the same maturity.

The corporate yield would have to be higher. Indeed, part of the higher yield that investors require on corporate bonds over Treasury bonds is related to the difference in tax treatment. The other reasons for the higher required yield are credit risk, liquidity risk and call risk (many corporate bonds provide the issuer with the ability to redeem the bond prior to maturity).

Liquidity Risk

In 2008, the market reminded investors that significant liquidity risk exists, even in investment-grade bonds. Not only did the spread related to credit risk between Treasuries and investment-grade bonds widen, as shown by the widening credit default swap premium, but the liquidity premium also widened. The weaker the credit, the wider both the credit and liquidity premiums became.

This is important for investors because it shows that, just as with stocks, corporate credit has significant tail risk. Corporate bonds’ tail risk has been well-documented in the literature, including by the May 2016 study “Can Higher-Order Risks Explain the Credit Spread Puzzle?” by Cedric Okou, Olfa Maalaoui Chun, Georges Dionne and Jingyuan Li. As one example, the authors cited the fact that BBB bonds saw their liquidity premium rise from 5 basis points before the 2008 financial crisis to 93 basis points during it.

I would add that, due to increased capital requirements for the banking industry, which historically had supplied most of the liquidity for corporate bonds, corporate bond liquidity has significantly declined. As a result, liquidity risk is now higher than it has been historically.

Furthermore, I’d observe that in 2008, the liquidity and credit risks inherent in corporate bonds showed up at a time when stock prices were collapsing, demonstrating that credit/default risk and equity risk are related.

Unfortunately, it looks like over the past 90 years that investors have not been adequately compensated for taking the various risks involved with corporate bonds. But the negative news doesn’t end there, as we have not yet fully considered the costs associated with implementing a corporate bond strategy.

Diversification Required With Corporate Bonds

Diversification is one of prudent investing’s most basic concepts. Because Treasury securities entail no credit risk, there is no need for diversification. As a result, investors do not need to employ a mutual fund. Instead, they can buy Treasury securities on their own—saving on mutual fund expenses.

However, corporate bonds entail credit risk and, thus, diversification is the prudent strategy. That requires the use of a mutual fund. Even low-cost mutual funds and ETFs can cost 10 to 20 basis points, wiping out much of the slim premium corporate bonds have earned. Because the trading costs for corporate bonds also are higher than they are for Treasuries, the realizable premium would be even slimmer, if any premium remains at all.

Summary

The Federal Reserve’s longstanding policy of zero interest rates left many investors hungry for yield and taking incremental risks. However, the historical evidence suggests investors may be better served by excluding corporate bonds from their portfolios, instead using CDs, Treasuries and municipal bonds as appropriate (given their marginal tax rate).

Alternatively, if you need or desire a higher return from your portfolio, instead of adding credit risk, the evidence suggests you should consider taking that risk with equities (for example, increasing your exposure to small and value stocks, and, today, to international developed and emerging markets with their lower valuations) rather than with corporate bonds.

However, if you are going to invest in corporate bonds, the evidence suggests you should stick with the highest-quality, investment-grade bonds (their risks, not just credit but liquidity risk as well, mix better with equity risks) and avoid callable bonds. Be sure you have not only considered the default risk inherent in corporate bonds, but the liquidity risk as well. As we discussed, these twin risks tend to show up at exactly the same time that equity risk does. While Treasuries tend to serve as a safe harbor during the storms that affect equities, corporate bonds do not. Thus, consider a portion of your corporate bond allocation equity risk, not bond risk. The lower the credit rating, the higher that percentage should be. Forewarned is forearmed.

This commentary originally appeared May 18 on ETF.com

By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party Web sites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them.

The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of the BAM ALLIANCE. This article is for general information only and is not intended to serve as specific financial, accounting or tax advice.