Portfolio Pain and the Difficulties of Discipline

Earlier this week, I discussed why it’s so hard to be a disciplined investor, which generally is a prerequisite for being a successful one. Building on this theme, the “Factor Views” section of J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s third-quarter 2018 review provides another example of why successful investing is simple, but not easy.

Value Investing Has Been Painful

Over the last 10 calendar years, Fama-French data from Dimensional Fund Advisors shows that the value premium in the U.S. was slightly negative, at -0.8%. The value premium (HML, or high minus low) is the annual average return on high book-to-market ratio (value) stocks minus the annual average return on low book-to-market ratio (growth) stocks.

Such long periods of underperformance will test the discipline of even those with a strong belief in the value factor. Compounding this issue is that, as the J.P. Morgan Asset Management report points out, since the beginning of 2017, the value factor has posted losses of nearly 15%.

Furthermore, the second quarter of 2018 was the value factor’s second worst since 1990. The result, the report states, is that “the factor is now mired in the second worst drawdown since 1990 (eclipsed only by the dot-com bubble).” The value premium’s poor performance was not confined to the U.S. The report’s authors also write that “the current drawdown is worse in Europe (-20%) and Japan (-21%) than it is in the U.S. (-17%).”

Importantly, the report’s authors offered this perspective: “In our view, this underscores that we are experiencing a natural sell-off of a factor whose performance is always cyclical.”

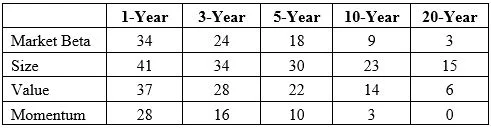

All risky assets and factors can go through very long periods of negative performance. You can see evidence of this in the following table, which covers the period 1927 through 2017. It shows the odds (expressed as a percentage) of a negative premium over a given time frame. Data in the table is from the Fama/French Data Library.

Occasional Underperformance Happens

Unfortunately, as I have discussed many times in my books and articles, investors often succumb to recency bias (the tendency to overweight recent events/trends and ignore long-term evidence). This leads investors to buy after periods of strong performance—when valuations are higher and expected returns are now lower—and sell after periods of poor performance—when valuations are lower and expected returns are now higher. Buying high and selling low is not exactly a recipe for success.

The correct way to think about the value factor’s recent underperformance is that, as the authors of the J.P. Morgan Asset Management report point out, “the opportunity set for the value factor continued to improve alongside the sell-off, as is typically the case for a mean-reverting factor such as value.”

They continue: “While value stocks are by definition cheaper than their more expensive counterparts, the gap in valuation is elevated relative to history (79th percentile dating back to 1990), which should point to above-average returns going forward. Historically, when the factor has been this cheap it has delivered average returns of 12% over the next 12 months and been positive 75% of the time. Further, gains in the value factor have tended to occur in batches—in fact, the top 20 months of performance account for 76% of the value factor’s gains since 1990. Given the above-average opportunity set … prospects for the value factor look particularly attractive at this point.”

Of course, this doesn’t guarantee the value factor will outperform in the near—or even the distant—future. However, it does increase the odds of that outperformance occurring. Because there are no clear crystal balls in investing, only cloudy ones, success is about putting the odds in your favor.

Curse Of Daily Liquidity

Two major benefits of owning mutual funds are that they provide daily liquidity and they can be traded at little to no cost. But the ability to sell on a daily basis can also be a curse for investors who lack discipline.

Consider how investors might behave if home prices somehow were computed daily and houses could be traded as easily and as cheaply as stocks. It is certainly possible that home price fluctuations would more closely resemble stock behavior than they do now in the absence of daily liquidity.

For example, imagine you own an investment property on Miami Beach and a major hurricane is poised to strike in the next few days. The price of homes in the area might take a significant hit. Most likely, you are not going to be tempted to sell. Instead, you would wait for the weather to clear. Perhaps investors do better with real estate than with stocks, because they find it more challenging to adopt the buy-and-hold strategy that works well in real estate and apply it to equities.

Summary

I hope my recent articles on the need for discipline will help you avoid mistakes associated with recency and resulting (as discussed in this article’s aforementioned companion piece). Ignore the noise of the market and work toward accepting even very long periods of underperformance as the “price” you pay for investing in risky assets in the expectation (but not guarantee) that you will be rewarded with a risk premium.

This commentary originally appeared August 1 on ETF.com

By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party Web sites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them.

The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of the BAM ALLIANCE. This article is for general information only and is not intended to serve as specific financial, accounting or tax advice.